How might a city agency make access to outdoor natural spaces a more safe, reliable, and inclusive experience for BIPOC visitors?

The Challenge

How might the Forest Preserves of Cook County (FPCC) make access to outdoor natural spaces a more safe, reliable, and inclusive experience for BIPOC visitors?

The Solution

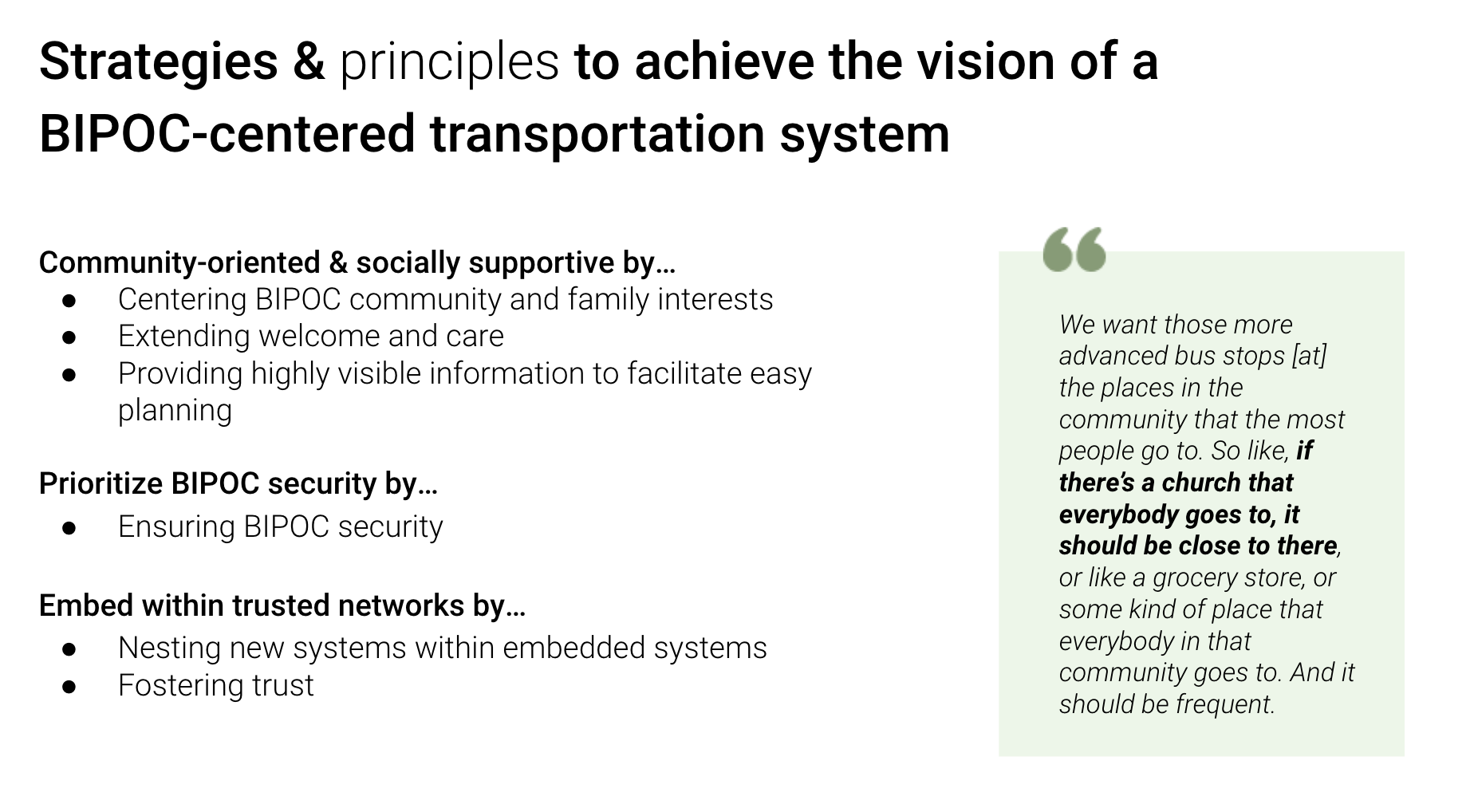

One vision, three principles and six strategies to guide future inclusive programming and policy-making at the FPCC. Read the full report here.

The Impact

FPCC staff used the strategies we crafted to evaluate their existing programming, which yielded insights about changes to current programming. Our team was invited to continue working on the project over the summer.

Time: 15 weeks, Spring 2022

Sector: Civic

Client: Forest Preserves of Cook County

My role: Design researcher

Services:

Participant recruitment

Workshop facilitation

Insight discovery

Strategic visioning

What makes this project unique?

Previous efforts by the FPCC to increase BIPOC visitorship had centered around one-time events such as BIPOC Yoga in the Park. Although these events were valuable, they didn’t address the systems-level elements that create racist outcomes. In contrast, this project provided an opportunity to create a systems-level vision for change led by the people with lived experience of the problem. The combination of the two things - a systems-level focus and BIPOC co-designers as the visionaries for change - yielded a compelling new vision for the FPCC, as well as a practical set of steps for realizing that vision.

1. Challenge

Systemic challenges: Totaling almost 70,000 acres, the Forest Preserves of Cook County (FPCC) is the oldest, largest forest preserve in the United States. Since their establishment in 1914, the Preserves have been an important place of natural connection for millions of city-dwellers. However, they remain largely inaccessible to many BIPOC Chicagoans as a result of redlining, violent policing, disinvestment in low-income neighborhoods and limited public transportation options. As a result, 85% of park visitors are White, even though White people only comprise 45% of the Chicago population (Black people are 29%).

How systemic barriers show up in daily life: Our team drew upon the work of a previous class of co-designers who investigated why many BIPOC Chicagoans choose not to visit natural spaces. They found that there are four main barriers:

Lack of adequate transportation to the parks

Lack of preparation and equipment

Lack of other BIPOC visitors to the park

Concerns about racial profiling and hate crimes

For this project, our goal was to convene a new group of BIPOC co-designers to envision solutions to these barriers. Our team focused in particular on transportation barriers to the parks.

2. Research + Insights

11 BIPOC co-designers

2 co-design workshops

5 physical prototypes

3. Solution

Sharing the vision with FPCC leaders

We presented this vision and set of strategies to leaders from the Forest Preserves of Cook County in an interactive workshop. After detailing our process and explaining the principles generated from the co-design workshops, we invited FPCC staff to evaluate one of their current programs using these principles.

It was exciting to see how this short exercise generated fruitful discussion and concrete ideas for how to make the FPCC more inclusive, equitable and anti-racist.

The FPCC was pleased with our work and invited our entire team to consult with them on another project during the summer.

4. Impact

Client Impact

The Forest Preserves of Cook County, the nation’s oldest park system that serves millions of visitors each year, has the tools and vision to create an anti-racist programming strategy that moves beyond one-time interventions.

These tools can be used to evaluate existing programming as well as create new programs.

The FPCC’s invitation to continue working on the project suggests that they saw value in co-design methodologies; hopefully this partnership will pave the way for future collaborations between FPCC and participatory design teams.

Personal Impact & Learnings

Learning about co-design helped me see more clearly the ways in which traditional human-centered design practices can be harmful. I hope to bring the co-design practices of hospitality, power sharing, capacity building and valuing lived expertise to as many future projects as possible.

With a limited budget and limited social networks beyond the Institute of Design, one of the biggest challenges we faced in this project was recruiting people for the workshops. If I were to do it again, I would seek out additional funding so we could compensate the co-designers more adequately for their time and provide additional incentives for participation.

Team

Team: Emery Donovan, Yonghak Kim, Sunaina Kuhn and Ron Martin

Final report prepared in collaboration with additional members of the co-design class: Elizabeth Graff, Luce James, Taka Kato and Latrina Lee

Faculty advisors: Chris Rudd & André Nogueira